Why audience is not the measurement – by Kerstin Stutterheim

Why I think that talking about the audience as a measurement or an aim is a mistake when it comes to writing and directing film or time-based media?

As a filmmaker as well as an academic myself, I often come across the demand to think about the audience before and while making a film or writing or conceptualizing art work. This always irritates me. Having been educated in the Faculty of Philosophy at Humboldt University Berlin and in one of the oldest and most established, but at the same time most modern, theaters, my immediate answer is that this is against all tradition. This may look like a very academic answer. From my academic and artistic education, my infinite reading, my excitement about great art – theatre, painting, performance, writing – I am deeply convinced that all great artists are in dialog with their audience in dealing with tradition and everyday life at the same time.

No one starts a work outside of life and reality. There is no ‚Kasper-Hauser‘-Artist. Perhaps sometimes the writer/director/artist comes from a different social group or environment than the decider or judge, but that doesn’t mean the artist is from outer space.

Starting to write or direct or perform takes place in communication with existing work. That means to get to know, to test and to challenge what the basic elements are that one has to respect. To respect means to think about what is basic and what can be changed and how, to be modified, to be tested or to be ignored, played with. Tradition gives a basic understanding and—to follow Kahneman’s concept of human thinking—it gives within the reception an impression of familiarity, cognitive ease.[i]

On that basis starting to try something new, different, surprisingly gives the ‘fast thinking’ a kick, the moment the associative system is invited to connect embodies knowledge and curiosity and to experience something new.[ii]

This fulfils thinking about audience, but more in an abstract or academic way. But this is not what—most often—the demand of thinking about the audience means when it comes to commissioning, film founding or production, teaching film & TV production etc. Will the audience understand and like this? Will they pay for it? Will they keep watching it? The last question includes money and a calculated economic success as well.

There is no such thing as THE audience. There is not one audience, everyone feeling the same or demanding the same story, aesthetic, style, whatever. Would you, my reader, choose the same book or the same story or the same style every day? Would you dress every day in the same colours? Or can you predict that next Friday you will for sure be up for wearing a red Jacket, eating potatoes for lunch, listening to the Beatles for driving to work, and watching a Tarantino film in the evening? Perhaps that day you’ll feel angry and then it will be the Rolling Stones or Bach? What about midsummer in two years? Will you be up that day for a romantic comedy or for a thriller, and should the main cast be Julia Roberts, Tom Hiddleston or Kit Herrington?

How can I as writer/director be sure that in one, two or five years THE AUDIENCE, on the day that my film will be screened, will still be up to the same calculated specific form? Thus, I have to rely on tradition, on basic knowledge and on artistic wisdom. And I will have to have a great story to tell, one that I am deeply convinced is a story worth years of intense work and my lifetime’s focussing on. What I am here calling artistic wisdom is very well reflected and not mystic or metaphysic knowledge. Philosophy is one discipline reflecting on aesthetics since ancient times, the other is a sub-discipline of philosophy called dramaturgy.[iii] Setting up a lot of new disciplines in opposition to, or thought as independent from, aesthetics and philosophy is taking away traditional and broad knowledge.

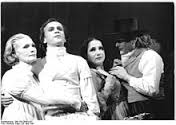

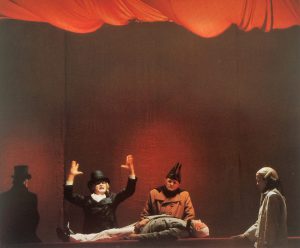

When I think about experiences with actual audiences, there are two different fields I can refer to, which I will do here in just a short overview. My first experiences go back to my time as dramaturgy assistant at the Deutsches Theater Berlin. There were some great directors, e.g. Thomas Langhoff, Alexander Stillmark, Johanna Claas, I had the opportunity of working with. But two were dominating the discourse, discussions and debates, fascinating the audience and splitting the colleagues into two groups. Friedo Solter was, in a nutshell, directing in a traditional way, modern, but moderate, up-to-date but not too provoking. He directed Wallenstein (Schiller)[iv] as well as Der aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui (Brecht)[v] in brilliant style. On the other side was Alexander Lang. He was the postmodern director of the ensemble. Provoking, excellent, fascinating. The first production of his I came close to was his interpretation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Shakespeare). There was a lot of brainwork done before they started to rehearse and during the process. And the audience liked it too. All performances of both directors were always sold out. And ran for a long time.

Shows I watched again and again as a member of the audience—more than ten times—were e.g. Arturo Ui directed by Friedo Solter; Dantons Tod [Danton’s Death] (Buechner)[vi] and Herzog Theodor von Gotland (Grabbe)[vii] both directed by Alexander Lang.

The audience was different every day. There were some evenings when most of the audience came because they were curious to see the new interpretation of something they knew or knew about, others came to see the actors in a new performance, others to see the new work of the directors and some just because they had a season ticket or someone had asked them out, it was a social event organised through work or an educational trip from school. And thus, the performance was a little bit different every day or perhaps just the atmosphere differed.

I have similar experiences from showing our own films. When a film is new, a premiere or a first screening at an important festival, the audience expects something special, they are mostly open minded, interested, excited, too.

And within our films there are always situations, scenes, dialogs, during which you can get an idea of the audience’s reactions at the screening. Do they get the joke or the irony in this dialog, do they see the emotional picture, do they hold their breath at this moment or not? And along that every discussion has a few similar questions, the standards, but more often completely different reactions, responds and queries. There are always differences and similarities between Berlin and Berlin, between Munich and Helsinki, Dubai, Tel Aviv, Szolnok, Dhaka, New York. Some US-media primed colleagues view European Documentaries as boring and old fashioned; others world wide are still working in poetic cinema, documentaries and fiction. Some filmmaker are still able to make poetic documentaries, being more visual, more artistic, and less outspoken or fast or hybrid; others invite these films to competitions in A-Festivals and sometimes these films receive an award too. One excellent example of a poetic documentary is “The Pearl Button” by Patricio Guzmán, awarded with the Silver Bear for Best Screenplay at the Berlin Film Festival 2015.

Teaching courses in Bangladesh, the UAE or Brazil, I found that the students were socialized and hence primed differently, but all of them were attracted by similar aspects of telling and directing a story. All of them discovered their specific style and narration to make their own projects, but all of them were in the given circumstances successful after they started to trust in artistic wisdom, the traditions, and the balance of constants and variants in storytelling. ‘The Secret of Storytelling’ as Jean-Claude Carrière puts it[viii], is this: it is the universal kernel of human communication, the interest in listening to and reading stories or watching narrative-performative work.

Sometimes a work needs the right time and place, some come perhaps too early or are rejected by journalists not prepared for this kind of art work; others are so well announced that critics and audience are overwhelmed by all this positive talk and don’t dare to question the work or themselves. One can see this easily with Kubrick’s movies. “Eyes Wide Shut” was criticised in the western world due to multiple reasons—some disliked Tom Cruise because of his private beliefs, others disliked Nicole Kidman, many disliked Kubrick since he never gave interviews to support his movies or the critics, others disliked the theme, the style, the amount of naked skin, a lot of immediately dislikes. The movie was not well received in the US, and Western Europe, thus it was marked as a flop. But this movie was successful—in Southern Europe, in Asia… How can anyone say you have to meet the interests of THE audience? Or Barry Lyndon—over decades described as difficult and not very successful—this film was just re-released and shown in cinemas. There is no such thing as THE audience which you can calculate upfront.

But, and this is the good news, we can trust that our audience in its variety, its broad interests and moods, will enjoy a good or excellently told story, when the auteur is aware of traditions and artistic wisdom, is creative and open minded, simply an artist, not a formatted industry worker. One has again to trust the writers, directors, the creative team and the artists, if we still want to get good and great stories told. Looking for a formula to calculate the mood and interests of the people is like reinventing alchemy.

Bibliography

BRECHT, B. 1965. Der aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui, (Frankfurt a. M.), Suhrkamp.

BÜCHNER, G. & MAXWELL, J. 1968. Danton’s death, London,, Methuen.

BÜCHNER, G., SMITH, M. W. & SCHMIDT, H. J. 2012. Georg Büchner : the major works, contexts, criticism, New York, New York ; London, W.W. Norton & Company.

CARRIÈRE, J.-C., BONITZER, P. & ALGE, S. 1999. Praxis des Drehbuchschreibens, Berlin, Alexander-Verl.

FUNKE, C., SOLTER, F., ENGEL, P., SCHILLER, F., DEUTSCHES THEATER (BERLIN GERMANY) & AKADEMIE DER KÜNSTE DER DEUTSCHEN DEMOKRATISCHEN REPUBLIK. 1982. Schillers „Wallenstein,“ Regie Solter, Deutsches Theater : Beschreibung, Text und Kommentar, Berlin, Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft.

GRABBE, C. D. & COWEN, R. C. 1975. Werke.

HASCHE, C., KALISCH, E. & WEBER, T. (eds.) 2014. Der dramaturgische Blick: Potenziale und Modelle von Dramaturgie im Medienwandel, Berlin: Avinius Verlag.

KAHNEMAN, D. 2012. Thinking, Fast And Slow, London, Penguin Books.

KLOTZ, V. 1998. Dramaturgie des Publikums: Wie Bühne und Publikum auf einander eingehen, insbesondere bei Raimund, Büchner, Wedekind, Horváth, Gatti und im politischen Agitationstheater, Würzburg, Königshausen und Neumann.

LESSING, G. E. & BERGHAHN, K. L. 1981. Hamburgische Dramaturgie, Stuttgart, Reclam.

REICHEL, P. (ed.) 2000. Studien zur Dramaturgie: Kontexte, Implikationen, Berufspraxis, Tübingen: Narr.

STUTTERHEIM, K. 2015. Handbuch angewandter Dramaturgie. Vom Geheimnis des filmischen Erzählens, Frankfurt am Main u.a., Peter Lang Verlag.

[i] KAHNEMAN, D. 2012. Thinking, Fast And Slow, London, Penguin Books.

[ii] Ibid., pp.50; pp79

[iii] LESSING, G. E. & BERGHAHN, K. L. 1981. Hamburgische Dramaturgie, Stuttgart, Reclam. HASCHE, C., KALISCH, E. & WEBER, T. (eds.) 2014. Der dramaturgische Blick: Potenziale und Modelle von Dramaturgie im Medienwandel, Berlin: Avinius Verlag, KLOTZ, V. 1998. Dramaturgie des Publikums: Wie Bühne und Publikum auf einander eingehen, insbesondere bei Raimund, Büchner, Wedekind, Horváth, Gatti und im politischen Agitationstheater, Würzburg, Königshausen und Neumann, REICHEL, P. (ed.) 2000. Studien zur Dramaturgie: Kontexte, Implikationen, Berufspraxis, Tübingen: Narr, STUTTERHEIM, K. 2015. Handbuch angewandter Dramaturgie. Vom Geheimnis des filmischen Erzählens, Frankfurt am Main u.a., Peter Lang Verlag.

Screenwriting manuals are the opposite of dramaturgy, more like painting by numbers

[iv] FUNKE, C., SOLTER, F., ENGEL, P., SCHILLER, F., DEUTSCHES THEATER (BERLIN GERMANY) & AKADEMIE DER KÜNSTE DER DEUTSCHEN DEMOKRATISCHEN REPUBLIK. 1982. Schillers „Wallenstein,“ Regie Solter, Deutsches Theater : Beschreibung, Text und Kommentar, Berlin, Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft.

[v] BRECHT, B. 1965. Der aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui, (Frankfurt a. M.), Suhrkamp.

[vi] BÜCHNER, G. & MAXWELL, J. 1968. Danton’s death, London,, Methuen, BÜCHNER, G., SMITH, M. W. & SCHMIDT, H. J. 2012. Georg Büchner : the major works, contexts, criticism, New York, New York ; London, W.W. Norton & Company.

[vii] GRABBE, C. D. & COWEN, R. C. 1975. Werke.

[viii] CARRIÈRE, J.-C., BONITZER, P. & ALGE, S. 1999. Praxis des Drehbuchschreibens, Berlin, Alexander-Verl., pp. 143

with many thanks to Saskia Wesnigk-Wood